-

Search

-

Recent Posts

- Kryptowährungen Handeln Test – Wo sind kryptowährungen verboten?

- Sichere Krypto Börse – Kryptowährung wovon abhängig?

- Kryptologie Uni Ulm | Welche kryptowährungen haben potenzial?

- Scalping Kryptowährung – Wie viele kryptowährungen gibt es bei coinbase?

- Margin Trading Kryptowährungen Yahoo Finance – Warum steigen kryptowährungen so stark?

Blog Archive

January 2026 M T W T F S S « Aug 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Categories

- Activities With Kids

- Adolescence

- Adulthood

- Aging

- Anger Management

- Apps

- Arts Education

- Babies

- Blog

- Books

- Boys to Men

- Breastfeeding

- Camp

- Cars

- Celebrity Dads

- Charity

- Child Development

- Children's Music Reviews

- Columns by Family Man

- Contests

- Creativity

- Dating Dad

- Death

- Divorced Dads

- Education

- Ethics

- Family Communication

- Family Man in the News

- Family Man Recommends

- Family Music

- Family Music Reviews

- Father's Day

- Featured Moms & Dads

- Film

- Food

- Free Stuff

- Friendship

- Gender

- Graduation

- Grandparents

- Halloween

- Health

- Helping Kids Understand Loss

- Holidays

- Humor

- Internet Safety

- LifeofDad.com

- Love and Courtship

- Marriage

- Morals

- Mother's Day

- Movies

- Music

- Newborns

- Over-parenting

- Parenting Stress

- Perspective

- Pets

- Politics

- Protecting Children

- Safety

- School

- Sex Ed

- Siblings

- Single Fathers

- Social Action

- Special Needs

- Sports

- Sweepstakes & Promotions

- Talking About Disasters

- Teens

- Top Ten Lists

- Travel

- Traveling With Kids

- TV

- Tweens

- Uncategorized

- Values

- Vasectomy

- Video

- What Dads Need to Know

- Work-Family Balance

Recent Comments

- Beth on The One That Ends With Hope

- Judi Feldman on The Brass Tacks of Music Education

- Fran Keer on A Road Well Traveled

- norman edelson on A Road Well Traveled

- Justin Rogan on The Gift of Boredom

- © 2026 - Gregory Keer. All rights reserved.

Acting From Within: Thoughts on Preventing Tragedy

By Gregory Keer

As hard as it is, the only way for me to sort through what happened in Newtown, Connecticut is to put myself in the middle of the tragedy.

Because I am a parent, I imagine I am the perpetrator’s mother, who looks at her son in the instant before he shoots her. I die before I can even think.

I am a teacher, and I shudder at what those charged with caring for those children must have thought in their last minutes as they sacrificed their lives in a desperate attempt to stop a madman.

I am a child in one of those first grade classrooms. Perhaps I have a fleeting blip of time to fear this man. Maybe I am the first to die, or maybe I am one of the other 19 children. In this case, I think, “Will he shoot me? Can I run away? He hurt my friend! Will someone save me?”

Now, I am a parent who hears my child has died. I feel blinding pain, hopelessness and anger, among so many other emotions — all of them searing. I think, “My child is gone forever? I sent my child to school, and he never came back. How can that be? How can I keep breathing? Please tell me this is not real.”

I am none of these participants. Yet, I am still a parent, a teacher, an American, a human being. And I feel so many things.

As I write this, the news is still horrifyingly fresh. There are so many unanswered questions. Some things, we will never know. What could have been in the mind of a young man, barely out of his teens, that would prompt him to slay 20 innocent children and six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary?

Even though we may never understand, I feel motivated, more the ever, to work to prevent this kind of tragedy from ever happening again. I fiercely believe this requires long-term thinking, and I worry too many people lack the patience and dedication to commit to that. Already, we are caught up in debates over whether better gun control will thwart a violently disturbed person from doing what he wants to do. While I believe we must improve background checks before selling guns to anyone, I want to focus on something we can all agree on.

As adults, we have a duty to fashion a world that’s safer and healthier for our children. We must make things better.

We have to care more about the well-being of people than we do now. We may never be able to stop a lunatic hellbent on destruction, but we can try much, much harder to do better as a society. We have to turn the discussion around so that we are not intent on preventing tragedy but working to promote goodness.

I know that to some, this may sound Pollyanna. I know I am flirting with idealism and optimism. So be it. What good is constantly reacting defensively to what is wrong in the world? Let’s go on the offensive to crush the kind of disconnection that makes outcasts of the mentally ill and socially misfit. We do woefully little to help those we cannot understand, and then we cry and shout when they hurt us.

Among the strategies are making mental health check-ups as normal as physical check-ups. They need to be affordable and not stigmatized. As a society, we are so averse to having anyone question whether we’re equipped to handle the ups and downs of life. We’re still supposed to fight through it without well-trained health professionals, and that’s not working — especially in an age where the resources exist but are not nearly as accessible or socially accepted as they should be.

Then, there are even more painstaking tasks we, as parents, must tackle with firm commitment. As President Obama said days after the shooting when he announced an interagency federal effort to combat violence, “Any actions we take must begin inside the home and inside our hearts.”

On a regular basis, we need to talk with our kids about their friends. We need to teach them how to be fair and caring. We must work with them on the nuances of resolving conflicts and understanding each other’s feelings. We must help our sons and daughters recognize and reach out to those who seem alone, and educate them about physical and mental differences that make people unique but no less worthy of our attention. In these ways, we might help our kids at the ground level to improve society’s connectedness.

We need to speak with the parents of our kids’ friends and classmates about their children. We should take notice when they are in need of support. We often get so wrapped up with our own needs, we fail to reach out the way our parents or grandparents did when society seemed smaller and more manageable. We have to create a village-like atmosphere where we help each other so that no parent or child feels outside the circle. If we encounter parents or children that resist social connection, then we should seek counsel or assistance to ascertain what might be causing it and do something to assist them.

We must rely on each other and on the professionals who can make our lives better, and be willing to seek help. Children come with a wide range of emotional and physical challenges. What matters is that we be proactive. This may result in our children needing therapy or medication — or even in us needing those things ourselves. If we make the effort to get help and act in our children’s best interest, we will not only be aiding them and ourselves, but the society around us.

It could take years, even decades for these strategies to take effect. But I have to believe that if we work together, we can create a better world for our children. The alternative is just too horrible.

A New Hope

By Gregory Keer

When it comes to donating money, I want to be impressive. Every December, when I send most of my biggest donations during the season of giving, I gather my children around and show them the websites and brochures of all the organizations I choose to support. In this way, they see what I value in the world and, hopefully, they think I’m a pretty nifty guy for sharing with those in need.

Sometimes, though, the philanthropic gestures of the dude they see eating potato chips in their living room at night is not impactful enough to truly teach how powerful giving to others can be.

Which is why, this year, I called upon the example of a hero my children and I have in common – the Star Wars navigator himself, George Lucas. This is a guy my kids relate to because he has entertained them with light-saber-bearing protagonists, wild alien creatures, and lots of swashbuckling space adventure.

So when I told them he is giving the entire $4.05 billion dollars from his sale of Lucasfilm to an educational charity, they were suitably impressed. Just think about what this says to the countless people influenced by the righteous rebelliousness of Luke Skywalker, the elegant leadership of Princess Leia, the daring bravado of Han Solo, and the Zen-like teaching of Yoda.

Lucas has dealt a serious blow to the dark forces Darth Vader represents by demonstrating that some people who hold great power really do want to heal the world. Already committed to education innovation via his Edutopia company that researches and promotes learning strategies, Lucas makes an even bigger statement about his belief that education must be a priority.

“I feel honored that he cares about kids even though they’re not his children,” my 11-year-old, Jacob, said. “He cares about how kids are going to be in the future.”

Through his donation, Lucas follows the Chinese proverb that says, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Although my wife and I have yet to find ourselves with a multi-billion dollar windfall to play around with, we do put a lot of thought into our philanthropic approach. Last December, as we gathered our sons around the table to select charities we wanted to emphasize, my kids were most taken with Save the Children. Not only did my boys like the idea of giving to other kids, they loved the catalogue that equated certain donation amounts with funding classrooms, buying goats and sheep, purchasing medicine, and making micro-loans for small businesses. These options helped my boys see the direct impact on families in America and throughout the world. So, instead of giving money, which often seems intangible to my kids despite all our best efforts to explain the value of it, my children gave animals that provided dairy products for a family and books for a village library.

During the year, my sons wondered how the recipients were doing with the animals and books. We discussed how the children would learn to milk the goat and sheep we bought for them. We imagined them laughing and being caught up in the adventure of the stories we made possible for them to read. The children we donated to were not “those poor people in underprivileged areas” — they were kids like our sons who got some important stuff because we shared with them.

While my sons and I can’t donate billions like George Lucas, we are inspired to continue giving to children so that they have a brighter future. This year, we’ll once again select gifts that will educate and sustain young people in need. In this way, we hope to ensure there’s more than “a new hope” ahead.

The Power of Stories: Flying Books and Ticking Clocks

By Gregory Keer

I’m sitting on the couch at 7:30pm, unable to do anything but stare at the TV changer, which is two feet in front of me, yet seemingly miles away.

“Must reach remote,” I say to myself. “Workday done. Dishes washed. Kids occupied. Basketball game starting…”

I muster the energy to lean forward when my mop-topped eight year old explodes through the living-room door.

“Daddy, let’s read!” Ari demands.

“Aren’t you old enough to read on your own?” I implore.

“No, I want to read with you,” he says, jutting out his lower lip to make a face he thinks tugs at my heartstrings.

It does.

Glacially, I rise from the couch, as if every muscle has been in hibernation for a season.

“Hurry, Dad, it’s getting late!” he shouts as he dashes ahead of me. Where does he get his reserve energy?

I make it to Ari’s room, moving like I’m underwater. I climb onto his bunk bed, clumsily arranging my adult body between stuffed animals and errant toys to get comfortable.

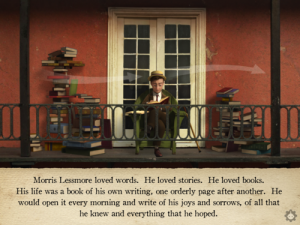

Then, we read William Joyce’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, about a writer whose library flies away in a hurricane. He is transported, Wizard of Oz-like to a world where he meets living books he comes to care for and that care for him as he grows old.

Then, we read William Joyce’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, about a writer whose library flies away in a hurricane. He is transported, Wizard of Oz-like to a world where he meets living books he comes to care for and that care for him as he grows old.

As grumpy as I was about having my me-time suspended, I generate some presence of mind to melt into the moment. It’s nice that my second grader, who loves devouring chapter books on his own, still wants his reading time with me.

When we finish, Ari asks, “Cuddle?”

Barely able to keep my eyes open, I agree, turn off the light, and proceed to fall asleep.

When I wake up, I’m as disoriented as a wayfarer who regains consciousness in a strange forest and curse myself for having lost 45 minutes of the evening.

I stumble from the bed, apologize to my wife — who’s working at the computer — for disappearing for so long. I check on my other sons, who are busy with homework and texting and my stomach churns over the fact that my plan to chat with them evaporated with my unexpected nap.

Bleary eyed, I break out the laptop to power through emails I just couldn’t finish during the day and don’t look up until I realize everyone in the house is asleep but me.

Lying down, I kiss my wife’s forehead, still bearing the frown of a complicated week and — can’t fall asleep. Knocked out of whack by the nap, I’m left with thoughts racing through my mind about everything I didn’t do and will likely be unable to do with so few hours in the day and so little energy in my aging body.

And then, I think about Morris Lessmore. Like Morris, I am often caught up in a hurricane of life. It carries away my days and, along with it, my ability to take stock in my children’s ascension to maturity. All too often, I find myself rushing my kids out in the morning and into bed at night just so I can get to – what? The end of the day, which will just bleed into another day of careening through responsibilities?

It’s a battle to leap from the cyclone, but it does happen for me, particularly when it comes to appreciating stories. It occurs in the moments I push myself past exhaustion to read a picture book with my youngest, watch and discuss a classic film with my oldest, and take in (with tears of pride) the short stories my middle child writes.

While not everyone is a writer, we all have the power to read books, watch movies and TV programs, and even to tell stories to our children, on everything from their days as infants to our own adventures through the years. Stories allow us to press the pause button on life and reveal our observations about what has happened and might come to be. While the whirlwind continues to whoosh around us, stories transport us to a quieter place of being together and acknowledging the tiny details that otherwise go unnoticed.

With the four days that Thanksgiving allows me with my family, I plan to do more cuddling with the kids — from the teenager to the second grader — to read, watch, and tell stories. Sweeter than any dessert, those moments will complete a holiday intended to help us all slow down and relish the most precious yet fleeting thing of all — time with those we love.

Night of the Shrinking Bed

By Gregory Keer

It was a cold, eerie night, eight years ago, an evening that still sends chills up and down my spine. My wife and I had endured a fifth straight evening of multiple wake-ups from our newborn. After two feedings, three walks around the house, and four false-alarm cries, Wendy and I trembled with exhaustion. This was compounded by the stress of having just moved to a new home, my starting a teaching gig, and our older sons kicking off a new school year.

Finally, sleep came and, when it did, I went down hard.

That was until I felt a “presence” hovering over me. Dog-tired, I kept snoring. Then I heard a faint wheezing. The wheezing turned to heavy breathing, which got louder and louder. High-pitched moaning pierced my eardrums and my eyes snapped open.

A dark shape stood next to me, holding what looked like an axe!

I screamed. “Ahhhhhh!!!!.”

My wife jumped up and shrieked, “Where’s the baby?”

The figure screamed back. “Dadddeee!!!”

Bolting upright, I recognized the shape as my son, Benjamin. The axe I imagined was his tattered blanket.

My son burst into tears and fell across me in the aftermath of what had been a twisted recreation of the movie scene in which Drew Barrymore sees E.T. for the first time. In this case, I was Drew Barrymore.

“What were you doing standing over me like that?” I said breathlessly.

“I – just – wanted – to – cuddle,” Benjamin blurted between sobs.

And there it was. The dramatic comeuppance for two parents who had long struggled with the issue of a family bed.

Before my wife and I had children, we swore we’d never let our kids sleep with us. We judged others who let their kids in the bed, thinking that kind of arrangement could only create intimacy problems for the couple and therapy sessions for the children.

Sometime later, we found ourselves changing our tune. It began when Benjamin, then almost three and new to a “big boy” bed without rails, started sneaking into our room in the middle of the night. Due to fatigue and the sheer joy of cuddling, we let him snuggle with us for a few hours each night. This went on for a couple of years until Jacob got old enough to leave the crib and want his own time in Mommy and Daddy’s bed.

So we started a campaign to keep the kids on their own mattresses. We told them that they could crawl in with us in the morning, when it was light outside. Jacob, always a deeper sleeper, was easier to keep to the new rule. But we had to experiment with all kinds of tricks to keep Benjamin in his room. Over time, we tried clocks, a sleeping bag on our bedroom floor, extra stuffed animals, a special pillow, and just plain begging with intermittent success.

Then, there was the previously mentioned night of all that wheezing and screaming.

After we all calmed down, I escorted Benjamin to his bed, reminding him of the house rules. A little later, he returned. I got crankier and he went away wailing again. This back-and-forth occurred every 10 minutes, as he tried to gain our sympathy and we used every tactic from yelling to listing all the playdates he was going to lose.

Then, my son Jacob joined the fray, shouting out like a lost child that his pull-up needed to be changed. Jacob fell back asleep but he was replaced by the dog that scratched at the door to go outside and the cat that upchucked a fur ball on the bed. All the while, my wife and I bickered about how to handle the whole mess.

I pleaded with our first-born. I even cried when he cried, asking for mercy on his exhausted father who had to wake up to teach cranky high-school sophomores in the morning.

Finally, with Benjamin as worn out as I was, I found clarity – kind of like a Bugs Bunny horror spoof in which the rabbit realizes the way to stop the monster is by complimenting him (“Gee, Doc, you got really big muscles.”) So, I appealed to Benjamin’s desire to feel like the big boy he was.

“You graduated from kindergarten and now you’re a first grader,” I explained. “It’s time to graduate to sleeping the whole night on your own. You can do this.” I then promised him a reward chart that would track how many nights he could stay in his bed.

Things got a lot better after that. For a while thereafter, Benjamin still crawled into bed with us at 6am or so, but he was proud of himself for becoming more “sleep independent.” Eventually, he stayed in his bed all night and my wife and I got our bed back…That is until kid number two started haunting us.

Spectator Sports

By Gregory Keer

Amidst all the splashing, dribbling, and leaping of this summer’s Olympics, one of the most memorable spectator sports involved Aly Raisman’s parents bobbing and weaving with every move their daughter made in her high-flying gymnastic pursuits. As a kid, I imagined what it might be like to flip and run like Olympians did, but as a (much less physically adept) adult, I identified with those parents. I felt the tension as they watched their daughters’ years of training be put to the test and I channeled their emotions with each result.

Amidst all the splashing, dribbling, and leaping of this summer’s Olympics, one of the most memorable spectator sports involved Aly Raisman’s parents bobbing and weaving with every move their daughter made in her high-flying gymnastic pursuits. As a kid, I imagined what it might be like to flip and run like Olympians did, but as a (much less physically adept) adult, I identified with those parents. I felt the tension as they watched their daughters’ years of training be put to the test and I channeled their emotions with each result.

I also ran a script in my mind of the conflicting thoughts they must have had:

“Is my child feeling too nervous? Is she proud of what she’s accomplishing?”

And…

“All that damn money and years of support had better have been worth it.”

There really is no way around this double-edged sword of a parent’s perspective. Try as we might to separate ourselves from our child’s endeavors, to be selfless, we have a lot invested. As such, it’s easy to get caught between what’s in it for our kids and what’s in it for us.

For parents, having children involved in sports — or any other extra-curricular endeavor that sucks up time like an industrial sponge — means serious parental sacrifice. You must shuttle them everywhere, sit there while they practice, and make sure it all works within the family’s schedule.

Somehow, my wife and I have navigated through a multitude of after-school athletics for our three boys. It’s often worn us out, but we’ve wanted them to try everything, to love sports and know how to play them for the benefit of their bodies, minds, and sociability. And, for me, I’ve enjoyed seeing my flesh and blood achieve on the playing fields.

But my perspective took on a new level of clarity a year ago, when our nine year old was recommended to join a competitive gymnastics team. For his part, Jacob was happy to be recognized for his accomplishment after months of hard work and we were pleased for him. Who wouldn’t be proud of their kid’s achievement?

Well, there was something else. There were our own feelings of how an ambitious team commitment would affect Jacob’s daily life and, yes, our lives. As two parents with full-time jobs and two other children to care for, this would have a domino effect on everyone.

So we went to a team orientation where more experienced parents explained that practices included two three-hour practices on weekdays and full-Saturday workouts. For meets, the time chunk would balloon and there would be travel throughout the year to places all over the region and, depending on how the team fared, to various parts of the country. If Jacob were to do well enough, he was looking at an even more rigorous regime in the years to come.

Wendy and I went home from that meeting with a sinking feeling. We just couldn’t imagine managing that kind of schedule. Also, we weren’t sure we wanted our son to endure so much competitive pressure in the pursuit of medals and the dim possibility of collegiate or Olympic glory. Further research revealed that the pounding his body would take often results in injuries, some of which could permanently affect him.

We went to our son and asked him, “Do you really want this?”

“I don’t know,” he said, a little anxiously.

We then explained our concerns, though we pledged that if it was something he strongly desired, we would find a way to make it work.

“Would I still be able to have dinner and go on vacations with the family?” he asked.

We were honest: “Probably not as often as we do now.”

“You’re my mom and dad,” he said. “I want you to decide what’s best for me.”

I have to admit I was tempted to sign him up, not just for him but for my dream of seeing my kid win medals. But the decision came down to the meaning behind our son’s primary questions.

Jacob has since gone on to play soccer, flag football, and run track. He says, now, he’d like to do gymnastics sometime, but not with a team. He wants to do it for fun.

Oh, yeah, fun.

No matter what we parents want for our children when they engage in sports, it has to be about enjoyment, above all else. Sure, one day, these athletic experiences may help our children compete better in all aspects of life and it may aid them in being excellent teammates and co-workers. But, unless it’s something a child has a singular passion for, no sport is worth giving up a balanced life of family, friends, school, and other hobbies. And it certainly isn’t worth it for the sake of a parent’s own sense of self worth.

Focusing on the kids’ joy and balance. Now those are things really worth cheering about.

The Tortoise Wins the Race

By Gregory Keer

At my son’s middle-school graduation, my wife and I performed our finest rugby moves to fight for seats with 2,000 other attendees. We were there to see our child walk across the stage in his suit, a little small on him but still dapper, and smile for the cameras we told him would be somewhere in the sea of smiling faces. After two hours of waiting, we saw him up there for an instant, a fleeting moment of culmination after three years of homework battles, shifting friendship circles, and adolescent changes that felt like alien transformation scenes.

At my son’s middle-school graduation, my wife and I performed our finest rugby moves to fight for seats with 2,000 other attendees. We were there to see our child walk across the stage in his suit, a little small on him but still dapper, and smile for the cameras we told him would be somewhere in the sea of smiling faces. After two hours of waiting, we saw him up there for an instant, a fleeting moment of culmination after three years of homework battles, shifting friendship circles, and adolescent changes that felt like alien transformation scenes.

During the ceremony, a few graduates gave entertaining speeches and administrators provided some touching words before reading an endless parade of 600 student names. Aside from the proud chatter of the families in the audience, people whispered one sad fact of the day – almost 200 kids could not participate in the proceedings because of academic issues.

How is it that 25% of this public-school 8th grade class did not pass muster? My thoughts ran the gamut for reasons, including lack of parental or teacher attention, student learning or behavioral challenges, and the intervention of trouble-making gremlins who force children to play video games instead of going to class.

Then I remembered that, 28 years ago, only half of my own high-school class graduated on time.

It makes me nuts that there exists such a long-standing tradition of kids not finishing school. I have lots of ideas of how to improve the state of education, from smaller class sizes to more creative educational methods. I know this takes a lot of money, but I believe good education pays amazing returns for the society and its economy.

I’m such a big believer in education that I became a teacher. I did it because I love learning and wanted to share it with students. I also did it because I wanted to learn ways to guide my own children toward academic success.

For all of my first-hand knowledge about teaching, the most important lesson is that those students who work really hard get results that include graduation, but go far beyond that. Sure, we teachers take pride in those who come up with high scores and brilliant ideas, but not all of those students have to labor for terrific results and, sometimes, those same kids leave a lot of potential untapped.

What really impacts educators are students who slog away, who may not get an “A” or “B” every time out, but who never stop fighting through difficult or – dare I say it? – boring material. These kids come to class on time, participate, show up at office hours, meet homework deadlines, and ask questions. Teachers recognize effort and want to help the kids who appear to want it the most. All of this adds up to students who know that hard work leads to better understanding of the material and a lifelong sense of what it takes to succeed in the years ahead.

During my son’s last year of middle school, he often wanted to get through his work as fast as possible. Sometimes, hastiness had no ill effect. But often, as in the case of assignments that required more detail but not necessarily more cognitive challenge, he lost steam and his grades fell. He regularly got less than excellent comments on his work habits, which, of course, drove me crazy. In the meantime, other students for whom great grades did not come easily, kept at it, tortoise style, and the outcomes were much better.

So, after a lot of errors on my part to motivate him, I focused on the value of effort. I told him I didn’t care about the grade as long as he pushed himself through the process with greater care. For the most part, this worked and – not surprisingly – things improved. Sure, I was happy to see the nice letter grades on the final report card, but what really had me beaming with pride were the work habit marks of “excellent.”

As Benjamin begins high school, where grades and achievement are ever more important, I must continue to stress the value of effort above all else. I think it will help my son arrive on time at graduation day, but I also believe it will work for more of those kids who may somehow give up – or be given up on by others – before they reach culmination.

If I have any advice for parents as we all embark on new school years, it is this – find your own ways to reinforce the goal of getting E’s for effort. Real effort that sometimes causes frustration, tears, and arguments are worth the price. We all benefit from it in the end.

National Treasures

By Gregory Keer

“Do I have to go? Nature’s overrated and hiking is boring.”

“Do I have to go? Nature’s overrated and hiking is boring.”

No, that was not one of my children, who complain about things just because we ask them to do it. This time, it was good ole city-boy me, moaning about Wendy’s suggestion that we head to the woods for a five-day excursion.

Sticking with her habit of ignoring my complaints, my wife scored a last-minute reservation at a lodge in an up-state national park. I had wanted anything else – a few days by the beach to doze or maybe a miracle European trip (hoping airfares would magically lower to 1970s prices). But Wendy, who works travel Web sites like a computer hacker, snagged this affordable trip to a land of dust, granite, and bad food.

When we announced our plans to the boys, they did something their father could not muster. They cheered and set about packing rugged clothes, flashlights, and survival food with the gusto of seasoned K2 climbers.

“Daddy, can I help you pack?” my middle son, Jacob (age 10), offered, sensing I needed a little push.

While it wasn’t enough to erase my internal resistance, seeing my kids rally to get on the road spurred me to ride the coattails of their enthusiasm. So I loaded up the iPod with music — a mix of songs the boys like and a bunch of Daddy’s R&B classics — dug out the neglected hiking shoes, and packed the SUV for adventure.

Less than seven driving hours later, we were in the park. Any remnants of grumpiness on my part were whisked away by the breeze wafting through our open windows. Tall pines, their tangy scent filling our senses, lined our route as we pulled over to make our first hike to an easily accessible but nonetheless impressive waterfall.

A little while later, we dropped our luggage in the dated yet comfy room and the kids rushed outside to play at a stream not more than 70 yards from our back door. Above us, mountains ringed the valley where we stood, replacing the office buildings we had in our recent memories.

“Look at the deer right in front of us!” Ari (7) announced as he scampered toward a pair of beautiful creatures munching on grass. With only one warning, as opposed to the six we usually have to shout to get him to comply, he stopped and stared at the deer as they enjoyed their late-afternoon snack.

Over the next few days, this national park vacation of ours – one that I had dreaded – climbed in my estimation. Every day, we combined fairly rigorous hiking with sitting by rivers and streams, taking in the endless natural curiosities around us. Little Ari made it up most of the mountain climbs, rarely objecting to the effort, and stalwartly dealing with wet clothes from the time he tripped into a pool of water.

A favorite trek was one I made with the two oldest boys. My frequently edgy teenager, Benjamin, was never so focused on a family effort as he was in leading us up a 2,425-foot climb. Feeling my age a bit, I relied on Benjamin and Jacob to inspire me up to the top, where we bore witness to a spectacular view. We took pictures and hugged each other, having conquered something bigger than just getting to school on time.

In our downtime, we sipped lemonades in the lodge while the kids read books about national parks. Truly fascinated, they never hesitated to teach us about the wildlife and geography they learned through the words on the page and the experience outdoors.

At the end of the stay, we stopped to see one last vestige of nature’s showmanship – a young bear scratching his butt on a fallen tree trunk. As the kids laughed, Benjamin, who seldom seems to enjoy time with his younger brothers and boring parents, suggested, “We should see a different national park every year.”

I’m certainly game to do this, because it confirmed what I sometimes forget. Kids are meant to play in nature. It calms them. It inspires them. The ground is meant to fall on, its earthy softness easy on young knees. The mountains and trees are meant to be scaled, rather than observed as pixilated images on video games. I owe more opportunities like this to my children.

In this month of our nation’s birthday, it’s fitting to praise “America’s best idea.” National parks are wonders worth beholding, whatever your camping aptitude is. They entertain as they teach and respect the average citizen’s budget. Although they need more financial support than ever, they do more for our children than we can ever repay. Most of all, they can turn cranky city dads like me into lovers of nature. Now that’s worth a proper salute.

The 5 Commandments of Fatherhood

By Gregory Keer

Ten years ago, I was getting woozy as I stared at the proof pages of a magazine I was editing. It was 4am. I had phoned my wife five times that night, promising to come home soon with each call. I really did love the work I was doing, but not seeing my kids for the whole day left me feeling empty.

The worst of the calls involved hearing my newborn wailing in the background as my then four-year-old got on the line to say, “You’re not even going to cuddle with us tonight?

I had been prepared for missing an occasional night with my kids. I wasn’t equipped to miss the three I was absent for in that week alone. In just a few days, I had broken most of the important rules I set for myself as a father.

It took me a while to change my ways (and eventually get a different job). Not to sound too much like an infomercial, but I did it by coming up with “5 Commandments” that led me – and can help you — to the promised land of involved fatherhood.

1. You Shall Keep Your Promises to Your Kids

Too often, we worry that our employers or clients will fire us if we don’t put them first when they ask for more of our time than we expect. Even more often, we think that we can make it up to our kids for the occasions we break a promise to be home at a certain time or take them out to play catch. That thinking is wrong. The reality is that the employer or client usually won’t fire you if you set limits (often they respect you more). Your kids, on the other hand, will lose faith in you if it happens too often.

My youngest son used to hover around my home-office, waiting to play with me at my work cut-off time. After a run of days doing that, he stopped waiting and went to his room to play alone. When I was ready for him, he told me, “Daddy, I want privacy. Shut the door.” That hurt. So, now, I try to put work on hold and play with him, rather than miss my opportunities.

Keep your promise to your kid and you won’t regret it. You can always catch up with the client after bedtime or schedule another time to follow up. Use technology (emails and faxes) to work overtime for us and help keep our kids happy.

2. You Shall Not Beat Yourself Up

We can do all the right things and still seem to “fail” with our kids (like when we come home with a great Chinese food and our kids say they no longer like Chinese food). Children don’t give us grades or raises. So there really is no consequence for small mistakes other than their grumpiness. Roll with the punches. If you yell at them or come home late, don’t write yourself off for long. Get back on track because you’ll get a lot of extra chances.

I go through periods where I raise my voice to my kids too often at night. I feel awful, but I do it because I’m out of control. Rather than not deal with them and their frustrating bedtime ways, I work on my expectations and approaches, tinkering every night. I also accept small victories — I’m happy for the nights I don’t yell and even happier for the nights they do almost everything I ask.

3. You Shall Establish a Rhythm

If you don’t jog regularly, your muscles forget what they’re supposed to do and bark back in pain. Similarly, if you don’t keep up regular parenting activities, it’s hard to build much strength in the relationships with your children. Give yourself a few assignments per day that involve helping your kids and you will get in their daily rhythm. Strive to have moments with them morning, noon, and night.

Try serving breakfast each day or every other day, driving them to or from school regularly, and reading to them or checking their homework each night. If you leave before the kids go to school, put a note in their lunch or call them from work before they go. You can even email or text your older kids each afternoon, just to check in. Phone calls and emails do not replace being there, but they can certainly keep you more in the loop than if you disappear from their lives for the day.

4. You Shall Hug a Lot

Men are notoriously stereotyped as undemonstrative. That’s often correct. If you are this way, consider the cliché of a hug a day. Kids need touch for security and love. Getting a hug — maybe more than one and throw a couple of kisses in there, too — means so much to a child in a cold world. You are their reliable source for validation, so give it.

Here’s a simple idea: when you can’t think of anything to say or do with your child — whatever they’re age — give your child a hug. They may sometimes push you away — as my 10-year-old sometimes does, especially around his friends — but what counts is that they know what you mean and it means the world.

5. You Shall Take Time Off

Quality time is what matters. Being focused on nothing but your kids for more than a couple of hours allows you to know them in a well-rounded fashion. So take a vacation, at least two solid weeks a year. And take occasional days off, maybe even once a month. When my buddy Sang had his first child, he was working crazy hours and was stressed out over the fact that he couldn’t see his kid during the day except on weekends. I suggested he take one day off each month or every two months. I also recommended he run home for lunch once a week or twice a month. In the scheme of things, it’s not much time from work and — now that he does it — it means a lot to him to be with his child just a little more.

Honestly, it remains a challenge for me to follow these “commandments” to the letter, but it does help me to stay focused on some rules I truly believe in. Try some of these ideas our and/or make up some of your own. The important thing to remember is that there is no higher authority than your own fatherly voice that says the time you spend with your children is precious enough to set in stone.

One of the Boys

By Gregory Keer

My wife complains about being the lone female in a house of four guys. She bemoans the bathrooms that have been territorially marked by boys with bad aim. She scowls at the criminal lack of fashion sense they possess. She shakes her head in futility over the pushing, punching, and head-locking the guys engage in more often than they speak to each other.

“I don’t know if I’ll ever get used to this,” she said, following a harrowing incident in which our seven-year-old chased her with a pair of socks that could have been mistaken for a round of Stilton cheese.

“I’ll never be able to pass along my Nancy Drew mysteries or my Little House books to a girl in pigtails,” she went on.

Then she glared at me. “It’s all your fault.”

This may be genetically true, in that the father determines the gender, though I’m hardly sympathetic. Growing up, Wendy was actually as much of a tomboy as a princess. Her childhood photo albums reveal a hard-nosed little leaguer, a dog lover who wrangled the Great Danes her family raised, and a kid who liked to tinker with socket wrenches. This is not to say that my wife didn’t wear dresses or try out her mom’s perfume. It’s just that Wendy is particularly well-suited to hanging with her homeboys.

For instance, it isn’t always the kids who start the rough-housing. Wendy picks fights with the boys, playfully challenging them to wrestling matches. Our youngest, Ari (7), loves it and doesn’t even mind when she pins him on the rug. Jacob (10) thinks the whole thing is just not right.

“Mommy, you’re a girl,” he says. “I don’t want to hurt you.”

To which Wendy responds by tackling Jacob, who is quickly reduced to a giggling mess.

Our 13 year old, Benjamin, has had quite enough of wrestling Mommy. He gets plain embarrassed when she tangles with him, especially because all 5’ 2” of her is competitive enough to still toss him around some.

Speaking of competition, my wife loves to coach the boys in athletics. Over the years, she’s mentored our kids in tee ball and soccer in addition to running them ragged in backyard basketball (she sucks at that sport, but enjoys harassing them on defense).

When it comes to fixing garbage disposals and door hinges, Wendy is the handy one. Ari loves to work alongside her with his own tool set, taking apart drawers and old toys for fun, showing how his engineering aptitude clearly comes from Mom.

I admit that some of these more traditionally male contributions tread on my ego as a dad. I’ve done a share of the wrestling and coaching, but when Wendy jumps in on these things, I feel a little left out. I’ve done everything from warning my wife that she might get hurt during the wrestling to nitpicking her methods on the field. And the day I tangled endlessly with the clogged toilet, reading instructions online and going through an assortment of plungers and coat hangers before I was flushed with success, I made sure to crow proudly to my sons that, yes, Daddy is a manly man who won’t be daunted by plumbing.

Fortunately, Wendy is big enough to let me work out my insecurities and deftly move to other ways of bonding with our boys. Among other things, she’s occasionally put aside her Twilight novels and headed down the path usually reserved for characters on The Big Bang Theory as she’s delved into science-fiction books and movies. This allows her to talk about aliens, wizards, and post-apocalyptic theories with Benjamin. Even in this gender blurring era, there aren’t too many mothers who can converse about wormholes and inter-galactic war.

Eventually, though, Wendy always returns to her moments of wishing she could interact with other females around the house (the dog and hamster just don’t do the trick). Frankly, I sometimes feel the same when I think of the missed opportunity to play the protective dad to a daughter or two.

But Wendy has gotten what she has always been well-suited for – a bunch of boys with whom she can put to good use all those years growing up as a girl who fit in with the guys. It’s helped her move past the occasional sexism in the workplace and it’s made her as strong as she is sensitive in other facets of her life. As a result, our boys see their mom as an example of how role models can come from both sides of the gender line. It’s the reason why this Mother’s Day is full of as many mud pies and bruises as Bath and Body Works. Wendy wouldn’t want it any other way. I know I wouldn’t.

When I’m 100

By Gregory Keer

My first grader came home recently with a completed assignment called, “When I Am 100 Years Old.” For it, he had drawn a picture of himself at the century mark, looking pretty much the way he does now, but with a long gray beard. Apparently, this is all it takes to distinguish a seven year old from a centenarian.

Under the picture was his life-topping accomplishment, “I will be a riter.”

In five words, my youngest son managed to reveal a treasure trove of insight. He told me his lifelong plans. He revealed that these schemes have to do with his connection to me, the guy he sees scribbling stories. And he showed he can’t spell worth diddlysquat.

This month marks my birthday. Because I am a “riter,” I’m spending time reflecting on how I’m doing goal-wise on my marchtoward (God willing) 100 years. There are areas I’m on target with, including keeping my marriage healthy, doing meaningful work, and making efforts on behalf of social causes. Among the aims I still want to achieve are learning to cook really well, playing at least one musical instrument, speaking Spanish, living in another city (if only for a season), and improving my free-throw shooting.

Above all, the category in which I’d like to improve most is fatherhood. It’s one reason I write these self-indulgent columns that chronicle the tinkering I do as a dad. While some of this labor is just me being nitpicky, a lot of it has to do with being better at following the biggest lesson I’ve learned about parenting – my children’s lives cannot be scripted. I cannot mold them in my image or in the image of someone I’d like them to be. I can give them plenty of good materials, but they have to craft themselves.

Having Ari say he wants to be a writer is nice now, but it’s likely he’ll do something different for a living. Ari loves to build stuff and take things apart to see what makes them tick. I have zero mechanical ability, so it’s hard for me to relate or even play alongside him when he reconfigures a door handle or surrounds his bed with various pulleys and other contraptions. My job is to let him horde boxes, tools, and various bits (which drives me nuts in that he keeps his room like a junk yard), so he can develop into who he wants to be. I’m fairly certain he will be some sort of engineer, though I’m trying to keep this kind of guessing to myself.

My middle son is most like me in his passions for writing stories, remembering lots of entertainment trivia, and having his feelings easily hurt. At the same time, his penchant for taking charge of situations and doing all his homework well ahead of schedule are far from my personal tendencies. Jacob currently thinks he’ll be an artist (architect, painter, or performer), while I imagine him becoming a creative businessman. Yet, he’s so full of interests and willingness to soak up information, he may be the kind of person who tries out a lot of things out. This could be difficult for making a consistent life, but it could also mean he’ll never be bored.

My 13 year old is the most open book of my three. He loves imaginative books, but prefers computers and science over discussing human nature. He doesn’t mind sports, though he veers away from competition. And he’s efficient at getting assignments done — when he feels it’s worth his time. As my eldest, he’s borne the brunt of my clumsiest parenting as I’ve pushed him the hardest on everything from studying more to maintaining better posture. Yet, this kid is more at ease than I ever was with a variety of friends and has a better sense of enjoying the world’s simple things. I worry he may lead a fairly modest life, but I’m confident he’ll rise to the level of happiness he wants for himself.

Too much of my early fatherhood years have been anchored in feeling I only have value if I show my sons the right way to do things. It’s often made me too intense in getting them to follow instructions and too judgmental of mistakes when I’ve warned them of pitfalls. All of this has been about making me more important to them than necessary.

For a dad – or any parent – that is a tough insight to internalize. I don’t know all the right answers, and even when I think I do, there is wisdom in keeping most of them to myself. Although I am bound by the parenting code that compels me to keep my kids safe and armed with good resources, I hope to mark the road to 100 with much more observing and cheerleading as my sons grow their own gray hairs.

Acting From Within: Thoughts on Preventing Tragedy

By Gregory Keer

As hard as it is, the only way for me to sort through what happened in Newtown, Connecticut is to put myself in the middle of the tragedy.

Because I am a parent, I imagine I am the perpetrator’s mother, who looks at her son in the instant before he shoots her. I die before I can even think.

I am a teacher, and I shudder at what those charged with caring for those children must have thought in their last minutes as they sacrificed their lives in a desperate attempt to stop a madman.

I am a child in one of those first grade classrooms. Perhaps I have a fleeting blip of time to fear this man. Maybe I am the first to die, or maybe I am one of the other 19 children. In this case, I think, “Will he shoot me? Can I run away? He hurt my friend! Will someone save me?”

Now, I am a parent who hears my child has died. I feel blinding pain, hopelessness and anger, among so many other emotions — all of them searing. I think, “My child is gone forever? I sent my child to school, and he never came back. How can that be? How can I keep breathing? Please tell me this is not real.”

I am none of these participants. Yet, I am still a parent, a teacher, an American, a human being. And I feel so many things.

As I write this, the news is still horrifyingly fresh. There are so many unanswered questions. Some things, we will never know. What could have been in the mind of a young man, barely out of his teens, that would prompt him to slay 20 innocent children and six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary?

Even though we may never understand, I feel motivated, more the ever, to work to prevent this kind of tragedy from ever happening again. I fiercely believe this requires long-term thinking, and I worry too many people lack the patience and dedication to commit to that. Already, we are caught up in debates over whether better gun control will thwart a violently disturbed person from doing what he wants to do. While I believe we must improve background checks before selling guns to anyone, I want to focus on something we can all agree on.

As adults, we have a duty to fashion a world that’s safer and healthier for our children. We must make things better.

We have to care more about the well-being of people than we do now. We may never be able to stop a lunatic hellbent on destruction, but we can try much, much harder to do better as a society. We have to turn the discussion around so that we are not intent on preventing tragedy but working to promote goodness.

I know that to some, this may sound Pollyanna. I know I am flirting with idealism and optimism. So be it. What good is constantly reacting defensively to what is wrong in the world? Let’s go on the offensive to crush the kind of disconnection that makes outcasts of the mentally ill and socially misfit. We do woefully little to help those we cannot understand, and then we cry and shout when they hurt us.

Among the strategies are making mental health check-ups as normal as physical check-ups. They need to be affordable and not stigmatized. As a society, we are so averse to having anyone question whether we’re equipped to handle the ups and downs of life. We’re still supposed to fight through it without well-trained health professionals, and that’s not working — especially in an age where the resources exist but are not nearly as accessible or socially accepted as they should be.

Then, there are even more painstaking tasks we, as parents, must tackle with firm commitment. As President Obama said days after the shooting when he announced an interagency federal effort to combat violence, “Any actions we take must begin inside the home and inside our hearts.”

On a regular basis, we need to talk with our kids about their friends. We need to teach them how to be fair and caring. We must work with them on the nuances of resolving conflicts and understanding each other’s feelings. We must help our sons and daughters recognize and reach out to those who seem alone, and educate them about physical and mental differences that make people unique but no less worthy of our attention. In these ways, we might help our kids at the ground level to improve society’s connectedness.

We need to speak with the parents of our kids’ friends and classmates about their children. We should take notice when they are in need of support. We often get so wrapped up with our own needs, we fail to reach out the way our parents or grandparents did when society seemed smaller and more manageable. We have to create a village-like atmosphere where we help each other so that no parent or child feels outside the circle. If we encounter parents or children that resist social connection, then we should seek counsel or assistance to ascertain what might be causing it and do something to assist them.

We must rely on each other and on the professionals who can make our lives better, and be willing to seek help. Children come with a wide range of emotional and physical challenges. What matters is that we be proactive. This may result in our children needing therapy or medication — or even in us needing those things ourselves. If we make the effort to get help and act in our children’s best interest, we will not only be aiding them and ourselves, but the society around us.

It could take years, even decades for these strategies to take effect. But I have to believe that if we work together, we can create a better world for our children. The alternative is just too horrible.

A New Hope

By Gregory Keer

When it comes to donating money, I want to be impressive. Every December, when I send most of my biggest donations during the season of giving, I gather my children around and show them the websites and brochures of all the organizations I choose to support. In this way, they see what I value in the world and, hopefully, they think I’m a pretty nifty guy for sharing with those in need.

Sometimes, though, the philanthropic gestures of the dude they see eating potato chips in their living room at night is not impactful enough to truly teach how powerful giving to others can be.

Which is why, this year, I called upon the example of a hero my children and I have in common – the Star Wars navigator himself, George Lucas. This is a guy my kids relate to because he has entertained them with light-saber-bearing protagonists, wild alien creatures, and lots of swashbuckling space adventure.

So when I told them he is giving the entire $4.05 billion dollars from his sale of Lucasfilm to an educational charity, they were suitably impressed. Just think about what this says to the countless people influenced by the righteous rebelliousness of Luke Skywalker, the elegant leadership of Princess Leia, the daring bravado of Han Solo, and the Zen-like teaching of Yoda.

Lucas has dealt a serious blow to the dark forces Darth Vader represents by demonstrating that some people who hold great power really do want to heal the world. Already committed to education innovation via his Edutopia company that researches and promotes learning strategies, Lucas makes an even bigger statement about his belief that education must be a priority.

“I feel honored that he cares about kids even though they’re not his children,” my 11-year-old, Jacob, said. “He cares about how kids are going to be in the future.”

Through his donation, Lucas follows the Chinese proverb that says, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

Although my wife and I have yet to find ourselves with a multi-billion dollar windfall to play around with, we do put a lot of thought into our philanthropic approach. Last December, as we gathered our sons around the table to select charities we wanted to emphasize, my kids were most taken with Save the Children. Not only did my boys like the idea of giving to other kids, they loved the catalogue that equated certain donation amounts with funding classrooms, buying goats and sheep, purchasing medicine, and making micro-loans for small businesses. These options helped my boys see the direct impact on families in America and throughout the world. So, instead of giving money, which often seems intangible to my kids despite all our best efforts to explain the value of it, my children gave animals that provided dairy products for a family and books for a village library.

During the year, my sons wondered how the recipients were doing with the animals and books. We discussed how the children would learn to milk the goat and sheep we bought for them. We imagined them laughing and being caught up in the adventure of the stories we made possible for them to read. The children we donated to were not “those poor people in underprivileged areas” — they were kids like our sons who got some important stuff because we shared with them.

While my sons and I can’t donate billions like George Lucas, we are inspired to continue giving to children so that they have a brighter future. This year, we’ll once again select gifts that will educate and sustain young people in need. In this way, we hope to ensure there’s more than “a new hope” ahead.

The Power of Stories: Flying Books and Ticking Clocks

By Gregory Keer

I’m sitting on the couch at 7:30pm, unable to do anything but stare at the TV changer, which is two feet in front of me, yet seemingly miles away.

“Must reach remote,” I say to myself. “Workday done. Dishes washed. Kids occupied. Basketball game starting…”

I muster the energy to lean forward when my mop-topped eight year old explodes through the living-room door.

“Daddy, let’s read!” Ari demands.

“Aren’t you old enough to read on your own?” I implore.

“No, I want to read with you,” he says, jutting out his lower lip to make a face he thinks tugs at my heartstrings.

It does.

Glacially, I rise from the couch, as if every muscle has been in hibernation for a season.

“Hurry, Dad, it’s getting late!” he shouts as he dashes ahead of me. Where does he get his reserve energy?

I make it to Ari’s room, moving like I’m underwater. I climb onto his bunk bed, clumsily arranging my adult body between stuffed animals and errant toys to get comfortable.

Then, we read William Joyce’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, about a writer whose library flies away in a hurricane. He is transported, Wizard of Oz-like to a world where he meets living books he comes to care for and that care for him as he grows old.

Then, we read William Joyce’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, about a writer whose library flies away in a hurricane. He is transported, Wizard of Oz-like to a world where he meets living books he comes to care for and that care for him as he grows old.

As grumpy as I was about having my me-time suspended, I generate some presence of mind to melt into the moment. It’s nice that my second grader, who loves devouring chapter books on his own, still wants his reading time with me.

When we finish, Ari asks, “Cuddle?”

Barely able to keep my eyes open, I agree, turn off the light, and proceed to fall asleep.

When I wake up, I’m as disoriented as a wayfarer who regains consciousness in a strange forest and curse myself for having lost 45 minutes of the evening.

I stumble from the bed, apologize to my wife — who’s working at the computer — for disappearing for so long. I check on my other sons, who are busy with homework and texting and my stomach churns over the fact that my plan to chat with them evaporated with my unexpected nap.

Bleary eyed, I break out the laptop to power through emails I just couldn’t finish during the day and don’t look up until I realize everyone in the house is asleep but me.

Lying down, I kiss my wife’s forehead, still bearing the frown of a complicated week and — can’t fall asleep. Knocked out of whack by the nap, I’m left with thoughts racing through my mind about everything I didn’t do and will likely be unable to do with so few hours in the day and so little energy in my aging body.

And then, I think about Morris Lessmore. Like Morris, I am often caught up in a hurricane of life. It carries away my days and, along with it, my ability to take stock in my children’s ascension to maturity. All too often, I find myself rushing my kids out in the morning and into bed at night just so I can get to – what? The end of the day, which will just bleed into another day of careening through responsibilities?

It’s a battle to leap from the cyclone, but it does happen for me, particularly when it comes to appreciating stories. It occurs in the moments I push myself past exhaustion to read a picture book with my youngest, watch and discuss a classic film with my oldest, and take in (with tears of pride) the short stories my middle child writes.

While not everyone is a writer, we all have the power to read books, watch movies and TV programs, and even to tell stories to our children, on everything from their days as infants to our own adventures through the years. Stories allow us to press the pause button on life and reveal our observations about what has happened and might come to be. While the whirlwind continues to whoosh around us, stories transport us to a quieter place of being together and acknowledging the tiny details that otherwise go unnoticed.

With the four days that Thanksgiving allows me with my family, I plan to do more cuddling with the kids — from the teenager to the second grader — to read, watch, and tell stories. Sweeter than any dessert, those moments will complete a holiday intended to help us all slow down and relish the most precious yet fleeting thing of all — time with those we love.

Night of the Shrinking Bed

By Gregory Keer

It was a cold, eerie night, eight years ago, an evening that still sends chills up and down my spine. My wife and I had endured a fifth straight evening of multiple wake-ups from our newborn. After two feedings, three walks around the house, and four false-alarm cries, Wendy and I trembled with exhaustion. This was compounded by the stress of having just moved to a new home, my starting a teaching gig, and our older sons kicking off a new school year.

Finally, sleep came and, when it did, I went down hard.

That was until I felt a “presence” hovering over me. Dog-tired, I kept snoring. Then I heard a faint wheezing. The wheezing turned to heavy breathing, which got louder and louder. High-pitched moaning pierced my eardrums and my eyes snapped open.

A dark shape stood next to me, holding what looked like an axe!

I screamed. “Ahhhhhh!!!!.”

My wife jumped up and shrieked, “Where’s the baby?”

The figure screamed back. “Dadddeee!!!”

Bolting upright, I recognized the shape as my son, Benjamin. The axe I imagined was his tattered blanket.

My son burst into tears and fell across me in the aftermath of what had been a twisted recreation of the movie scene in which Drew Barrymore sees E.T. for the first time. In this case, I was Drew Barrymore.

“What were you doing standing over me like that?” I said breathlessly.

“I – just – wanted – to – cuddle,” Benjamin blurted between sobs.

And there it was. The dramatic comeuppance for two parents who had long struggled with the issue of a family bed.

Before my wife and I had children, we swore we’d never let our kids sleep with us. We judged others who let their kids in the bed, thinking that kind of arrangement could only create intimacy problems for the couple and therapy sessions for the children.

Sometime later, we found ourselves changing our tune. It began when Benjamin, then almost three and new to a “big boy” bed without rails, started sneaking into our room in the middle of the night. Due to fatigue and the sheer joy of cuddling, we let him snuggle with us for a few hours each night. This went on for a couple of years until Jacob got old enough to leave the crib and want his own time in Mommy and Daddy’s bed.

So we started a campaign to keep the kids on their own mattresses. We told them that they could crawl in with us in the morning, when it was light outside. Jacob, always a deeper sleeper, was easier to keep to the new rule. But we had to experiment with all kinds of tricks to keep Benjamin in his room. Over time, we tried clocks, a sleeping bag on our bedroom floor, extra stuffed animals, a special pillow, and just plain begging with intermittent success.

Then, there was the previously mentioned night of all that wheezing and screaming.

After we all calmed down, I escorted Benjamin to his bed, reminding him of the house rules. A little later, he returned. I got crankier and he went away wailing again. This back-and-forth occurred every 10 minutes, as he tried to gain our sympathy and we used every tactic from yelling to listing all the playdates he was going to lose.

Then, my son Jacob joined the fray, shouting out like a lost child that his pull-up needed to be changed. Jacob fell back asleep but he was replaced by the dog that scratched at the door to go outside and the cat that upchucked a fur ball on the bed. All the while, my wife and I bickered about how to handle the whole mess.

I pleaded with our first-born. I even cried when he cried, asking for mercy on his exhausted father who had to wake up to teach cranky high-school sophomores in the morning.

Finally, with Benjamin as worn out as I was, I found clarity – kind of like a Bugs Bunny horror spoof in which the rabbit realizes the way to stop the monster is by complimenting him (“Gee, Doc, you got really big muscles.”) So, I appealed to Benjamin’s desire to feel like the big boy he was.

“You graduated from kindergarten and now you’re a first grader,” I explained. “It’s time to graduate to sleeping the whole night on your own. You can do this.” I then promised him a reward chart that would track how many nights he could stay in his bed.

Things got a lot better after that. For a while thereafter, Benjamin still crawled into bed with us at 6am or so, but he was proud of himself for becoming more “sleep independent.” Eventually, he stayed in his bed all night and my wife and I got our bed back…That is until kid number two started haunting us.

Spectator Sports

By Gregory Keer

Amidst all the splashing, dribbling, and leaping of this summer’s Olympics, one of the most memorable spectator sports involved Aly Raisman’s parents bobbing and weaving with every move their daughter made in her high-flying gymnastic pursuits. As a kid, I imagined what it might be like to flip and run like Olympians did, but as a (much less physically adept) adult, I identified with those parents. I felt the tension as they watched their daughters’ years of training be put to the test and I channeled their emotions with each result.

Amidst all the splashing, dribbling, and leaping of this summer’s Olympics, one of the most memorable spectator sports involved Aly Raisman’s parents bobbing and weaving with every move their daughter made in her high-flying gymnastic pursuits. As a kid, I imagined what it might be like to flip and run like Olympians did, but as a (much less physically adept) adult, I identified with those parents. I felt the tension as they watched their daughters’ years of training be put to the test and I channeled their emotions with each result.

I also ran a script in my mind of the conflicting thoughts they must have had:

“Is my child feeling too nervous? Is she proud of what she’s accomplishing?”

And…

“All that damn money and years of support had better have been worth it.”

There really is no way around this double-edged sword of a parent’s perspective. Try as we might to separate ourselves from our child’s endeavors, to be selfless, we have a lot invested. As such, it’s easy to get caught between what’s in it for our kids and what’s in it for us.

For parents, having children involved in sports — or any other extra-curricular endeavor that sucks up time like an industrial sponge — means serious parental sacrifice. You must shuttle them everywhere, sit there while they practice, and make sure it all works within the family’s schedule.

Somehow, my wife and I have navigated through a multitude of after-school athletics for our three boys. It’s often worn us out, but we’ve wanted them to try everything, to love sports and know how to play them for the benefit of their bodies, minds, and sociability. And, for me, I’ve enjoyed seeing my flesh and blood achieve on the playing fields.

But my perspective took on a new level of clarity a year ago, when our nine year old was recommended to join a competitive gymnastics team. For his part, Jacob was happy to be recognized for his accomplishment after months of hard work and we were pleased for him. Who wouldn’t be proud of their kid’s achievement?

Well, there was something else. There were our own feelings of how an ambitious team commitment would affect Jacob’s daily life and, yes, our lives. As two parents with full-time jobs and two other children to care for, this would have a domino effect on everyone.

So we went to a team orientation where more experienced parents explained that practices included two three-hour practices on weekdays and full-Saturday workouts. For meets, the time chunk would balloon and there would be travel throughout the year to places all over the region and, depending on how the team fared, to various parts of the country. If Jacob were to do well enough, he was looking at an even more rigorous regime in the years to come.

Wendy and I went home from that meeting with a sinking feeling. We just couldn’t imagine managing that kind of schedule. Also, we weren’t sure we wanted our son to endure so much competitive pressure in the pursuit of medals and the dim possibility of collegiate or Olympic glory. Further research revealed that the pounding his body would take often results in injuries, some of which could permanently affect him.

We went to our son and asked him, “Do you really want this?”

“I don’t know,” he said, a little anxiously.

We then explained our concerns, though we pledged that if it was something he strongly desired, we would find a way to make it work.

“Would I still be able to have dinner and go on vacations with the family?” he asked.

We were honest: “Probably not as often as we do now.”

“You’re my mom and dad,” he said. “I want you to decide what’s best for me.”

I have to admit I was tempted to sign him up, not just for him but for my dream of seeing my kid win medals. But the decision came down to the meaning behind our son’s primary questions.

Jacob has since gone on to play soccer, flag football, and run track. He says, now, he’d like to do gymnastics sometime, but not with a team. He wants to do it for fun.

Oh, yeah, fun.

No matter what we parents want for our children when they engage in sports, it has to be about enjoyment, above all else. Sure, one day, these athletic experiences may help our children compete better in all aspects of life and it may aid them in being excellent teammates and co-workers. But, unless it’s something a child has a singular passion for, no sport is worth giving up a balanced life of family, friends, school, and other hobbies. And it certainly isn’t worth it for the sake of a parent’s own sense of self worth.

Focusing on the kids’ joy and balance. Now those are things really worth cheering about.

The Tortoise Wins the Race

By Gregory Keer

At my son’s middle-school graduation, my wife and I performed our finest rugby moves to fight for seats with 2,000 other attendees. We were there to see our child walk across the stage in his suit, a little small on him but still dapper, and smile for the cameras we told him would be somewhere in the sea of smiling faces. After two hours of waiting, we saw him up there for an instant, a fleeting moment of culmination after three years of homework battles, shifting friendship circles, and adolescent changes that felt like alien transformation scenes.

At my son’s middle-school graduation, my wife and I performed our finest rugby moves to fight for seats with 2,000 other attendees. We were there to see our child walk across the stage in his suit, a little small on him but still dapper, and smile for the cameras we told him would be somewhere in the sea of smiling faces. After two hours of waiting, we saw him up there for an instant, a fleeting moment of culmination after three years of homework battles, shifting friendship circles, and adolescent changes that felt like alien transformation scenes.

During the ceremony, a few graduates gave entertaining speeches and administrators provided some touching words before reading an endless parade of 600 student names. Aside from the proud chatter of the families in the audience, people whispered one sad fact of the day – almost 200 kids could not participate in the proceedings because of academic issues.

How is it that 25% of this public-school 8th grade class did not pass muster? My thoughts ran the gamut for reasons, including lack of parental or teacher attention, student learning or behavioral challenges, and the intervention of trouble-making gremlins who force children to play video games instead of going to class.

Then I remembered that, 28 years ago, only half of my own high-school class graduated on time.

It makes me nuts that there exists such a long-standing tradition of kids not finishing school. I have lots of ideas of how to improve the state of education, from smaller class sizes to more creative educational methods. I know this takes a lot of money, but I believe good education pays amazing returns for the society and its economy.

I’m such a big believer in education that I became a teacher. I did it because I love learning and wanted to share it with students. I also did it because I wanted to learn ways to guide my own children toward academic success.

For all of my first-hand knowledge about teaching, the most important lesson is that those students who work really hard get results that include graduation, but go far beyond that. Sure, we teachers take pride in those who come up with high scores and brilliant ideas, but not all of those students have to labor for terrific results and, sometimes, those same kids leave a lot of potential untapped.

What really impacts educators are students who slog away, who may not get an “A” or “B” every time out, but who never stop fighting through difficult or – dare I say it? – boring material. These kids come to class on time, participate, show up at office hours, meet homework deadlines, and ask questions. Teachers recognize effort and want to help the kids who appear to want it the most. All of this adds up to students who know that hard work leads to better understanding of the material and a lifelong sense of what it takes to succeed in the years ahead.

During my son’s last year of middle school, he often wanted to get through his work as fast as possible. Sometimes, hastiness had no ill effect. But often, as in the case of assignments that required more detail but not necessarily more cognitive challenge, he lost steam and his grades fell. He regularly got less than excellent comments on his work habits, which, of course, drove me crazy. In the meantime, other students for whom great grades did not come easily, kept at it, tortoise style, and the outcomes were much better.

So, after a lot of errors on my part to motivate him, I focused on the value of effort. I told him I didn’t care about the grade as long as he pushed himself through the process with greater care. For the most part, this worked and – not surprisingly – things improved. Sure, I was happy to see the nice letter grades on the final report card, but what really had me beaming with pride were the work habit marks of “excellent.”

As Benjamin begins high school, where grades and achievement are ever more important, I must continue to stress the value of effort above all else. I think it will help my son arrive on time at graduation day, but I also believe it will work for more of those kids who may somehow give up – or be given up on by others – before they reach culmination.